6.1. Complex Numbers and Complex Functions¶

\(\DeclareMathOperator{\arctantwo}{arctan2}\)

6.1.1. Algebra¶

To quote Wikipedia:

In its most general form algebra is the study of symbols and the rules for manipulating symbols and is a unifying thread of all of mathematics.

An example is simple arithmetic we are all used to. We all know that \(a\times b=b\times a\), i.e. if \(a\) and \(b\) are the numbers we all think of then the order in a multiplication is irrelevant. We could device of set of symbols and manipulation rules where this property is not true.

The algebra of complex numbers is close to the algebra of the real numbers (in which the commutative property of multiplication does hold).

Basically what we do to define complex numbers is that we add a new ‘number’ that we call \(j\) to the real numbers (in control theory it is called ‘j’, in classical math literature it is called ‘i’). We can add \(j\) to a real number like \(2+j\). This is not a real number of course and there is no way to simplify this in any way. But what is it? Essentially, mathematicians don’t care, they want a neat self consistent structure (an algebra) so they can do calculations.

We can also multiply a real number with the complex number \(j\) and get \(3j\), again something we can’t simplify.

But what happens when we multiply \(j\) with itself? What is \(j\times j = j^2\)? If this can’t be simplified we open up a box of pandora because then what is \(j j j = j^3\). Instead of introducing just one new symbol in our calculations, we essentially introduce a lot of them: \(j\), \(j^2\), \(j^3\), etc. And what to think of \(j^\pi\)?

Fortunately complex numbers are more neat than this. We define

- the imaginary number \(j\) has the property that \(j^2=-1\).

Note that this really is a remarkable definition. When you are accustomed to real numbers it is no wonder we call it an imaginary number: indeed a strange thing that the square of a ‘number’ is negative. But for now just play along with this mathematical game; these complex numbers turn out to be very useful in practice indeed.

Given this definition we have \(j^3 = j^2 j = -1 j = -j\). Note that we haven’t said what \(j^\pi\) is, but can you really explain what \(2^\pi\) is? We get to that later.

If you think of it the general form of a complex number is simple:

- A complex number \(z=a+jb\) has a real part \(\Re(z)=a\) and a

complex part \(\Im(z)=b\) where \(a\) and \(b\) are real numbers. Any complex number :math:`z` can be written as :math:`a+jb`.

Complex numbers are used so often they got their own name:

- The set of all complex numbers is denoted as \(\mathbb C\)

Algebraically the complex numbers follow the same rules as the real numbers (mathematicians say that the set of all complex numbers form a field):

- we can add two complex numbers to give a new complex number. We define: \((a+jb)+(c+jd)=(a+c)+j(b+d)\).

In adding a complex number we add the real and imaginary parts (and we do know how to do that because these are real numbers by definition).

- there is a unique additive identity element \(0\) such that for all complex numbers \(z\) we have: \(z+0=z\).

The identity element of course is \(0+j0\).

- there is an additive inverse element \(-z\) such that \(z+ (-z)=0\).

Obviously in case \(z=a+jb\) we have \(-z=-a-jb\).

- the addition and multiplication are commutative (\(a+b=b+a\)) and associative (\(a+(b+c)=(a+b)+c\)).

The associative property implies that in an addition of several complex numbers we may leave out all parentheses. The commutative property and the commutative property combined make that in a summation of several complex numbers we may permute the numbers in the sum.

- we can multiply two complex numbers to give a new complex number: \((a+jb)(c+jd)=(ac-bd)+j(ad+bc)\)

There is really nothing special in the multiplacation. Just follow your high school math method to get rid of parenthesis (in Dutch high schools there are two prevailing tricks: the ‘snavel’ method and the table method): \((a+jb)(c+jd)=ac + jad + jbc + jbjd = (ac-bd)+j(ad+bc)\)

there is multiplicative identity element \(1\) such that \(1z=z\)

there is a multiplicative inverse element \(z\inv\) for every \(z\not=0\) such that \(z z\inv = 1\):

\[(a+jb)\inv = \frac{1}{a+jb} = \frac{a-jb}{a^2+b^2} = \frac{a}{a^2+b^2} - j \frac{b}{a^2+b^2}\]There is a lesson to be learned here. No matter how complicated an algebraic expression using complex numbers may get that expression always represents a complex number and thus we should be able to find the real values \(a\) and \(b\) such that the complex number is \(a+jb\). And there a few ‘tricks’ that you can use to do so (or use Mathematica or Wolfram Alpha...). The trick to write \(1/(a+jb)\) as a real number in the standard form is to multiply the denominator with \(a-jb\).

- the multiplication distributes over the addition: \(u(v+w) = uv+uw\).

Ah, of course this is what we used essentially when defining the multiplication of two complex numbers.

- The complex conjugate \(z^\ast\) of a complex number \(z=a+jb\) equals \(z^\ast=a-jb\).

We have used this before (without nowing what name it is given). Let \(z=a+jb\) then \(zz^\ast = a^2+b^2\): a real number.

- Roots of Polynomials. Whereas for real numbers the equation \(z^2=-1\) has no solution, for complex numbers we can find two roots: \(z=i\) and \(z=-i\). Remember that a quadratic equation didn’t have solutions when the determinant is negative? Well in \(\mathbb C\) there is always a solution and a negative determinant merely indicates that some roots are complex values. In fact in \(\setC\) an \(n\)-th order polynomial has exactly \(n\) roots (taking multiplicity of roots into account).

6.1.2. Geometry¶

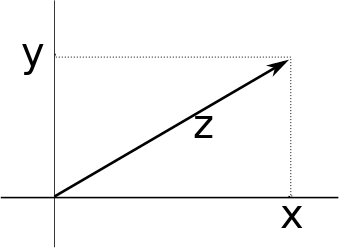

Complex number \(z=x+jy\) as vector in \(\mathbb{R}^2\)

As we have said before any complex number \(z\) can be written as \(z=x+jy\) where \(x\) and \(y\) are two real numbers. Therefore:

- A complex number \(z=x+jy\) can be interpreted as a point \((x,y)\) in two dimensional space \(\mathbb{R}^2\).

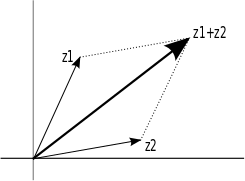

Addition of two complex numbers

We can plot a complex number as a point or vector in 2D space. The vector interpretation of interpretation of complex numbers may help in interpreting addition and subtraction.

- Addition (and subtraction) of complex numbers can be interpreted as addition (and subtraction) of vectors in \(\mathbb{R^2}\).

We can also characterize the complex number \(z\) as the vector in \(\mathbb{R}^2\) with lenght \(r\) and angle \(\phi\) with the positive \(x\)-axis:

- Polar representation: \(z=r e^{j\phi} = r\cos\phi + jr\sin\phi\), where \(|z| = r =\sqrt{x^2+y^2}\) and \(\phi=\arg(z)=\arctantwo(y,x)\)

This polar representation makes it easy to see what multiplication and division of complex numbers does in the complex plane.

- Multiplication of two complex numbers \(z_1=r_1 e^{j\phi_1}\) and \(z_2=r_2 e^{j\phi_2}\) results in the complex number \(z = z_1 z_2 = r_1 r_2 e^{j(\phi_1+\phi_2)}\), i.e. the lengths multiply and the angles add up.

The division is left as an exerise to the reader...

6.1.3. Complex Functions¶

We are accustomed to look at functions as mappings from the set of real numbers to the set of real numbers. Complex functions do exist as well, so we can define a function \(f:\setC\rightarrow\setC\):

indeed for every \(z\in\setC\) the function gives a complex value \(f(z)\). A complex function is not so easy to plot: every complex value \(z=x+jy\) is mapped to a new value \(f(z) = x'+jy'\) where \(x' = f_r(x,y)\) and \(y'=f_i(x,y)\). In terms of real valued functions a complex function is the combination of two real valued functions in two variables. Please note that this is not the prefered way to look at complex functions. Just consider complex functions as a kind of slot machine where you put in one complex number (\(z\)) and the machine will return you another complex number (\(f(z)\)).

As we started by defining the algebraic operations on complex numbers, all functions that are compositions of these basic algebraic operations are complex functions. But what about the sin function or the exponential functions or the logarithmic function. Can we take the sin of a complex number? And what would it mean then?

And of course: “Yes we can!”. Complex function theory is a rather complex theory and for all details we refer to standard books on this subject. Here we point at a common way to define complex functions. We start with a real function, say \(\sin(x)\), then expand this function in a series using only algebraic operations on the argument \(x\) making sure the series for is valid for any \(x\in\setR\). Then we define the complex function using the algebraic series of the real valued function.

Take the real valued sine function \(f(x)=\sin x\). Its Taylor series expansion is:

Mathematicians can prove that this series converges to the true value for any \(x\). Note that the right hand side of the above equation makes perfectly sense if we replace \(x\) with a complex value \(z\). So we define the complex sine function as:

Of course this only makes sense in case this series converges for all values of \(z\). The series definition of the sine function is not the way you would like to calculate the sine function of course. Fortunately it can be shown that

where \(\sinh\) and \(\cosh\) are the hyperbolic sine function and hyperbolic cosine functions (look them up on Wikipedia in case you want to knwo). These functions are implemented in any decent math library.

Along the same line of reasoning we can define the complex exponential function:

We get a famous result in case we set \(z=j\phi\) (a pure imaginary number):

In the second series on the right hand side of the above equation we recognize the series of the sine function. The first series is equal to the cosine function. This leads to the famous Euler’s formula:

In (digital) signal processing we will use complex functions quite a lot. Mostly we will consider the `nice’ functions that behave along the lines we would expect from our calculus course. But be warned: complex functions can really be quite complex:

No this is certainly not true, but it is an error because a result from real analysis is used that is not generally true for complex functions. For complex arguments \(\sqrt{ab}\not=\sqrt{a}\sqrt{b}\).